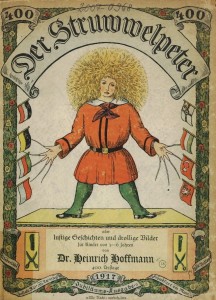

Struwwelpeter is a classic example of the cautionary tale. It’s a collection of illustrated stories in verse showing misbehaving children and the dreadful consequences they suffer. First published in 1845, its original title was Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder mit 15 schön kolorierten Tafeln für Kinder von 3-6 Jahren (Funny Stories and Whimsical Pictures with 15 Beautifully Coloured Panels for Children Aged 3 to 6).

Maybe I was born in the wrong era. Although I find the book amusing now, as a child I found the pictures ghastly, especially the ones accompanying “Daumenlutscher” (Thumb-sucker) and “Die gar traurige Geschichte mit dem Feuerzeug,” a story of a girl who plays with matches and is burned to death. The final picture in this story shows the girl’s two cats beside her ashes, crying a great pool of tears.

It’s the illustrations that really stay in my mind, probably because I could not read German as a child. But I didn’t have to know German to understand the message of the stories: look what happens to misbehaving children!

I was prompted to read Struwwelpeter again, oddly enough, after reading Martyrs Mirror for the first time.

Martyrs Mirror is one of those books, I suspect, that many people know about but considerably fewer people actually read (so I was mildly surprised to find that the public library’s sole copy was checked out). It is a huge work, over a thousand pages, with 104 illustrations. The full title is The Bloody Theater, or, Martyrs’ Mirror of the Defenseless Christians Who Baptized Only Upon Confession of Faith, and Who Suffered and Died for the Testimony of Jesus, Their Saviour, From the Time of Christ to the Year A.D. 1660. It was compiled by Thieleman J. van Braght, a Dutch Mennonite pastor, in 1660.

The book is a compilation of stories and letters, some brief and some running to several pages. It begins, as the title says, with the earliest Christians and moves chronologically from there, devoting considerable attention to the 16th century.

The etchings, by Dutch artist Jan Luiken, are skilfully done and quite arresting. Some are rather gory— for instance, the illustration of the apostle Bartholomew being skinned alive and beheaded. Others are gruesome more for what they suggest than for what they show. One shows the children of a Maeyken Wens, searching for her tongue screw among her ashes after she was burned to death.

In a way, Martyrs Mirror reverses the message of Struwwelpeter. The children’s book says “be good, or face dire consequences.” The accounts of martyrs say “be good, like these martyrs, and be prepared to face dire consequences as they did.”

That, in a sense, is the point of the book. Martyrs Mirror was written a century after the worst of these persecutions took place. The introduction says that it is meant particularly for believers who had become safe, prosperous, and complacent, so that they will be reminded of the faith of their forebears. Although it’s difficult for us to see it that way today, van Braght meant the book to be an encouragement as well as a warning.

Brilliant linking the two, Joanne. I found Struwwelpeter funny even when I was little because the rhymes are hilarious, but I confess to many mixed feelings about following the martyrs’ examples. I like your summary of the author’s message, but if I had a child, I’d rather tell her, “Be good, and continue to be good when it gets hard. But for goodness sake, when you see them coming to kill you, get out of the way!” There’s no cause for which one wants to make murderers, surely. And I think I’m still being faithful to the tradition, since that’s exactly what lots of Mennonites did, and how I came to be born in Tadjikistan.