The church I attend sings a lot of hymns translated by John Mason Neale (1818-1866). That probably says something about the type of hymns we tend to sing, but it also says a lot about how prolific he was as a translator, and how much the English-speaking church owes him.

The church I attend sings a lot of hymns translated by John Mason Neale (1818-1866). That probably says something about the type of hymns we tend to sing, but it also says a lot about how prolific he was as a translator, and how much the English-speaking church owes him.

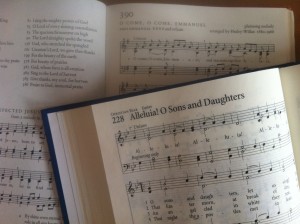

The current Anglican hymnal, Common Praise, for instance, has no less than 25 texts translated by Neale. (Hymns Ancient and Modern had many more than that, judging by a brief glance at its index.) The old red Anglican hymnal, which my church still uses, has twenty. Over half of these are hymns marking seasons of the church year: Advent, Lent, and especially Easter. Hymnal: a Worship Book, used by Mennonite churches, has only eight, but one of those is “O Come, O come Emmanuel,” one of the essential Advent hymns.

One result of the 16th-century Reformation was that Protestant churches began using vernacular languages in church liturgy instead of Latin. This was a good thing on the whole, but some things were lost in the process. A great wealth of ancient hymns “henceforth became as a sealed book and as a dead letter,” as Neale regretfully put it. He did his best to remedy that, translating over two hundred Latin and Greek hymns from the early centuries of Christianity.

I would guess that many people sing these hymns without realizing just how old they are. “O Sons and daughters” is relatively new, written in the 16th century, but “That Eastertide with joy was bright” dates back all the way to the 4th century. Thanks to these translations, English-speakers have access to hymns spanning over sixteen hundred years.

Every era of church history has had its own “brand” of hymody, with its own particular emphases and its resulting strengths and weaknesses. The greater the variety of hymns we can sing, the greater the breadth of language and imagery that can inform and enrich our faith.

[The title of this post borrows a phrase from Exploring the Mennonite Hymnal: Handbook (Faith and Life Press, 1983, now out of print), p. 59]